How to Criticize Religion

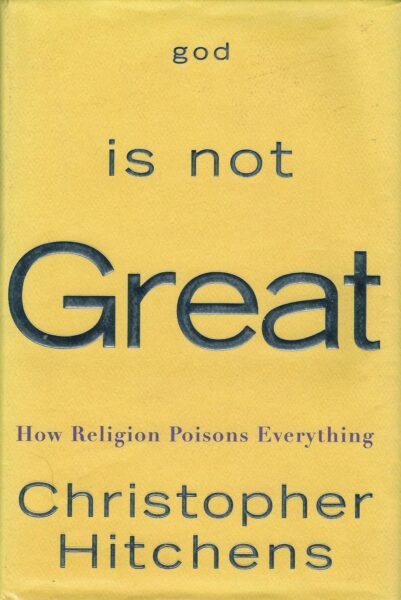

Nathan Jacobson » Reflections on Christopher Hitchens' God is not GreatChristopher Hitchens’ god is not Great is an expression of the profoundest moral outrage at the transgressions of religious people. As such, Hitchens follows in a long and honorable tradition. Indeed, in his life and teaching, Jesus also was a consummate critic of corrupted religion. In particular, it was the religious authorities of his time and place — the pharisees — that he most roundly denounced. His criticisms were many, but included charges of hypocrisy, pride, legalism, and unkindness. Like Hitchens, a consistent theme in Jesus’ criticism is how inhumane their religious strictures had become. For example, in one of a number of confrontations over Sabbath observance, Jesus reminds the pharisees that the Sabbath was instituted for the sake of humankind, not vice-versa. Furthermore, the letters of early church leaders follow Jesus’ precedent in confronting the failings of his earliest followers. And they all stood in a long line of prophetic voices that, according to the biblical record, were called by God to correct the recurring degeneration of Hebrew, and then Christian, religion. Finally, today you can browse the bookshelves of any Christian bookstore to find volume after volume lamenting this or that shortcoming of the Church. Clearly religion can be corrupt, even poisonous, and it is hardly exempt from criticism. But though Hitchens is in good company in his indictment of religious transgressions, god is not Great is something of a missed opportunity. Because his rhetoric evinces such a profound contempt for people of faith, Hitchens fails to speak persuasively to the very people he thinks need saving. If intended merely as a call to arms for his compatriots, god is not Great is a tour de force. But if he hopes to deconvert the converted, to liberate those captive to religion, another course is needed. If that is the aim, here’s how to criticize religion.

1. Be a “Friend of Simpletons”

Though Hitchens’ criticism of religion is an honorable venture, his approach is markedly different to that of Jesus. One of the most intriguing aspects of Jesus is the reputation he earned as a “friend of sinners”. Jesus had strong words for those who, like himself, claimed to speak for God. But he was notorious in his time for befriending, dining and drinking — yes, really drinking — with tax collectors, prostitutes, and other social pariahs of first century Palestine. To the pharisees’ chagrin, such people were drawn to Jesus, and he welcomed their company. As he said himself, he came for the lost. It’s easy to miss the power and subversiveness of the way of Jesus. Times have changed. The notion of “sin” sounds medieval to modern, and especially postmodern, ears. What hasn’t changed is that each of us harbor hostilities toward certain members of society whom we deem repugnant. If not the taxman, it’s our political adversary. If not the prostitute, it’s the child molester. I confess a perhaps peculiar resentment for the spammer. As a web developer, I’ve had my share of forums for which I was responsible defiled. It doesn’t matter if you’ve built an online playground for pre-school kids, if you leave the gate ajar, before long you’ll be flooded with 24 point type offering free gang bangs and bestiality with just a click. Every year, businesses lose tens of billions of dollars in lost productivity and on filtering spam. Spammers throw a thousand tons of excrement a second against the world wide wall in the hopes of finding one in a thousand who likes the taste. For the rest of us, it stinks. To be honest, I’d struggle to dine with the likes of them without giving them a piece of my mind. And if we search our souls, we find that we all have such people for whom we harbor disdain, “sinners” in our eyes.

Pharisees Among Us

For Hitchens, the “sinners” are a vast swath of humanity, those guileless sheep still beholden to religious faith, and especially the shepherds who beguile them. From his writings, interviews, and debates, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Hitchens can hardly stand them. He has mined every nook and cranny of the english language for every possible pejorative to express his contempt. Meanwhile, Hitchens has nothing but pats on the back for his fellow secularists, saving all his vitriol for those who have not been so enlightened. The contrast with Jesus could not be starker. Hitchens is akin to the pharisee, looking down his nose at the unwashed masses, denouncing their willful ignorance, their simple faith. They are sick, “poisoned” by religion. He has come to save the sick and the lost with the good news of the Enlightenment, and in this his intentions are noble. But his strategy, it would seem, is to shame them, to make them so embarrassed that they will abandon their faith if for no other reason than to escape his scorn, his lashing tongue. No doubt his rhetoric will be an antidote for some, but most will reject even a dose because the doctor seems more cruel than kind.

Hitchens and his cohorts like to say that religion has nothing to teach us about ethics that we didn’t already know. However, in Jesus we see something completely unexpected, something that challenges our natural selves. We don’t befriend those whom we consider “sinners”. We don’t love them. We don’t treat them with respect. We judge and reject. Pharisees are still among us. Some are religious, some are not. They are us. Richard Dawkins, for example, typifies this reaction in his shunning of former atheist Antony Flew. In 2005, Flew had the gall to travel to Biola, an evangelical Christian university, where he accepted the Phillip E. Johnson Award for Liberty and Truth. This was too much to let pass: cavorting with conservative Christians, accepting an award named after the godfather of the Intelligent Design movement. For his sins, Dawkins dubs Flew “ignominious”, and intimates at senility (The God Delusion,pp. 106, 123). Michael Ruse has been similarly lambasted as an appeaser and “clueless gobshite” for his too friendly disposition toward the ID theorists and creationists with whom he contends. I applaud Hitchens’ willingness to spar and debate with the defenders of religion in a variety of venues, from Christianity Today to Kings College, and even the aforementioned Biola. But, what if, like Jesus, Hitchens were to come alongside those he considers to be suffering the ill-effects of religion’s toxicity not as the consummate critic but also as a faithful friend? I can envision a senior seminar at Biola University or Notre Dame discussing at length with Doug Geivett or Alvin Plantinga the prospects for religion in this, the twenty-first century, all things considered.

Interestingly, the reviled Flew is an example of just such a friendly disposition. Though for most of his life he was unsparing in his reasoned criticism of theism, from an early acquaintance with the late C.S. Lewis to the warm friendships he developed with Gary Habermas and other Christian thinkers, Flew apparently didn’t let his idealogical differences devolve into enmity. On a recent episode of the Michael Medved Show (Sep. 28, 2009: Hour 3), a caller asked Christopher Hitchens this very question of befriending rivals. The caller described himself as an atheist who was increasingly concerned by the anti-religious vitriol and judgmentalism he finds amongst his atheist friends compared to the equanimity of his Christian acquaintances. Based on his experience, the caller asked: “Do you make an effort to associate and make friends with Christians?” Hitchens responded: “I don’t make a special effort, no. I was brought up amongst them. I was educated with them. I have a number of friends who are quite devout. … These people that you’re hanging out with sound to me like the insipid, cultural Christians that you meet all over the place that are effectively no better than Unitarians.” It would seem, unfortunately, that for Hitchens, his sharp disagreement precludes befriending the “simpletons”. Only the mealy-minded can cross the barricades.

The Pitiful Truth

The keys to being able to befriend and treat with kindness those whom we are inclined to detest, I think, are love and pity. We’ll get to love, but pity? This is counterintuitive, to be sure. We naturally revolt against being pitied. Indeed, we often say something like: “Detest me, revile me, but whatever you do, don’t pity me.” It is the ultimate insult to our pride. So, to be clear, I’m not recommending that the critics of religion make a habit of channeling Mr. T: “I pity the fool.” Rather, I’m speaking of an unspoken pity that is grounded in a stark awareness of one’s own pitifulness. Christians come at this realization in part from their belief that we are fallen, all of us. Their pity, or empathy, then, is grounded in the belief that we are all shadows of our ideal selves. To the extent that Christians trade in self-righteousness and judgmentalism, they have failed to apprehend this central Christian claim. But I do not think such an awareness requires a religious view. Surely a survey of humankind reveals that we are, on the one hand, misshaped by imperfect and sometimes terrible life experiences; and on the other, we ourselves fail to follow our best instincts and sometimes willfully submit to our worst.

Following Jesus’ lead, John Dickson commends just such a disposition to Christians when reflecting on Hitchens’ recounting of the ignominious deeds committed in their name.

Modern believers have to face the facts and admit that the church has often failed to live up to Christ’s standards. … “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 5:3). The kingdom, Jesus says, belongs not to those who think of themselves as morally and spiritually rich, but to those who look into their souls and find poverty. (“Religion and Violence” at CPXtra, Oct 28, 2009)

I’d like to think that Hitchens himself is aware of ways in which he falls short of his own moral and epistemic aspirations. And yet, there is little evidence of empathy in his rhetoric. His intellectual self-righteousness prevents it: “And here is the point, about myself and my co-thinkers. Our belief is not a belief. Our principles are not a faith… we distrust anything that contradicts science or outrages reason. We may differ on many things, but what we respect is free inquiry, open mindedness, and the pursuit of ideas for their own sake. We do not hold our convictions dogmatically…” (GISG, p.5) Hitchens’ self-appraisal is a noble ideal, but let’s be frank: neither he nor his co-thinkers are perfect paragons of the way of science and reason. It is too much to rehearse Hitchens’ biases and shortcomings in reasoning here, but the bevy of books published in response to god is not Great enumerate them at length. Some of them at least, hit the mark. And the point is, that’s to be expected. He’s human, and yes, flawed. But as long as we see ourselves as perfectly righteous, or perfectly reasonable, we will be unable to come alongside the unenlightened as trusted friends and will be left throwing stones from a distance with the pharisees. If what religious people need is a kind of “intervention” to ween them from their addiction to “blind faith”, friends are precisely what is needed.

Sales or Suasion

Considering the tremendous success of god is not Great in terms of sales, it is tempting to think that it could not have been more effective. If Hitchens had written more empathetically and irenically, no doubt it would not have been such a bestseller. The popularity of certain radio shows and political blogs is ample evidence that demagoguery is a reliable recipe for popularity. But, does it persuade? Does it change hearts and minds? It remains to be seen what kind of enduring impact Hitchens’ brand of criticism will have on the ranks of the religious in the years to come. I suspect that, for the most part, it will merely have served to deepen the entrenchment between the secular and the religious. If Hitchens is right that religion is an irrational relic that “always” ravages or retards the good of society, that failure of persuasion is a tragedy. In his life and teaching, Jesus offered another way. And, if the remarkable spread ofChristianity in the first and second centuries is any indication, that way has the power to transform the thinking of cities, nations, and empires. The way of Jesus commends itself all the more since the best antidote for irrationality would be careful and patient instruction in a thoughtful and reflective life. Though Jesus is, of course, a religious figure, religion’s critics could benefit from appropriating his way of persuasion. And if the effort failed, at least we would be left as friends.

2. Tell the Whole Story

Hitchens’ catalog of the misdeeds of religious people is like a Headline News version of the religious world. If it bleeds it leads. The local evening news predictably leads with a recounting of the police blotter, before, of course, getting around to the weather. When the weather is severe, it leads. Based on the news, you would never know that the city in which I live is an exceedingly safe and pleasant place. International news is even more one dimensional. Often it seems the only way to register in the international headlines is to either experience or commit a great tragedy or atrocity. And so, in the popular consciousness: drought stricken Ethiopia was but a vast wasteland populated by children with distended bellies; Apartheid South Africa was an endless landscape of riots on dusty streets; Bangladesh is just a swampland perpetually inundated by floods; Los Angeles was aflame in riots from San Diego toSanta Barbara after the Rodney King verdict, and what was left has been burned to the ground ever since by unrelenting wild fires. I’ve often wondered if there is a certain level of schadenfreude at the root of this kind of reporting. “My life may not be perfect, but at least I don’t live in a dreadful place like that.” Perhaps it makes us feel better about our own lot in life to be reminded constantly of the suffering and wickedness of others. Having lived in a number of international locales, I’ve often been frustrated by how poorly places I know well are perceived from afar. This type of journalism is no small part of the problem. And as a journalist, Hitchens seems prone to exactly this kind of reporting. Apparently, only when religion fails is it newsworthy.

A Tendentious Tale

As someone nurtured from birth in a religious community, I’m in a privileged place to judge whether Hitchens’ account of religion tells the story well. I have a wealth of first-hand experience of the subject matter. Do I recognize myself or those I know anywhere in Hitchens’ two-hundred-eighty some pages? I don’t. A number of times while reading god is not Great, I’ve wondered how I would fare if I ever merited the attention of Hitchens’ pen. I’m an average bloke, a mix of strengths and weaknesses, virtues and vices. But, as a person of faith, I suspect that somehow I would emerge in his account as some kind of degenerate, an utter failure of a human being. If Mother Theresa and Billy Graham are reduced in this way, certainly he could manage a hatchet job in my case as well. To wit, my mother occasionally ponders politically incorrect thoughts about the causes of urban poverty. My brother is a driven and successful executive for a sometimes cutthroat corporation. My sister-in-law is a bit obsessive about health and diet. I am a single male, chaste even in my mid-thirties. Sometimes I interrupt people mid-sentence. I can imagine Hitchens’ summation of me and my family: “They are but an inbred clan of unrepentant racists and craven materialists, gullibly taken in by fad diets and superstition. As for Nathan, he’s obviously repressed and full of himself, a willing victim of impossible sexual taboos and religious certitude.” If you think this imagined caricature is exaggerated, then you probably haven’t read Hitchens.

While such an account might have grains of truth, it wouldn’t be the whole story, not even the real story. My mother’s questions and sometimes impolite thoughts are the result of laboring for fifteen years in the inner city, working, in the name of Jesus, to give disadvantaged youth an exit from poverty’s revolving door. Now she and my father work in South African townships, educating young people on the front lines of the AIDS epidemic. Her heart breaks for the people she serves and loves. My brother and sister-in-law are both fine specimens of humanity, whatever their faults. I won’t defend my own foibles, but my experience of other Christians couldn’t be more contrary to Hitchens’ account of religion and its effects.

A Different Story

From a young age I was philosophically inclined, profoundly interested in life’s big questions. My parents always encouraged my studies and helped me acquire books to that end. When my curiosity led to questioning my own childhood faith, none of the Christians in my life ever scolded my doubtfulness, but rather encouraged me to seek answers. At the local Christian seminary I checked out George Smith’s Atheism: The Case Against God and Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian, along with C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity and Craig Blomberg’s The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. A Princeton and later Cambridge grad who was studying there mentored me throughout high school and college, modeling and encouraging academic excellence and intellectual honesty and humility. After receiving my BA in philosophy at a well regarded public university, I went on to pursue an MA in philosophy at a Christian college where the academic standards were far higher, and the spirit of learning and truth seeking sacrosanct. I have never wanted for Christian mentors and peers who sought a faith that was reasonable and true.

My moral aspirations have my whole life been elevated by biblical exhortations and the example of Jesus and those who follow him today. I learned about the genocide and inhumanity in Darfur not from the evening news or George Clooney, but from Christian aid workers who were on the ground in Sudan many years before it became a cause célèbre, purchasing slaves to free them and providing humanitarian aid. My conscience was horrified reading Disposable People, a book I discovered in Books and Culture: A Christian Review. And my solidarity with the enslaved peoples of the world has been sustained by the work of International Justice Mission, who are risking everything to live out the biblical mandate to “seek justice, protect the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow”. Christian concerts I attended when I was young were often preceded by a call from Compassion International to sacrifice some of the earnings from our minimum-wage jobs to provide food, health care, and education for a child in the third world. My church youth group spent some of its weekends serving food at the inner city homeless shelter or mopping floors at a “street school” for high school dropouts.

My mind and moral convictions have been nurtured by a Christian family and community from the beginning; not to mention the unconditional love and security my brothers and I felt in our home, never concerned for a moment that my parents would be unfaithful to us or each other. In each case, these good people who contributed to my upbringing believed they were living out what it means to follow Jesus. Meanwhile, Hitchens has the temerity to answer his own question, “Is Religion Child Abuse?”, in the affirmative, without the slightest qualification.

Where are the Christians who have populated my life in Hitchens’ considerations of whether religion is palliative or poison? The tragedies and atrocities of religion to which Hitchens almost exclusively draws our attention are a part of the story to be sure, but they are not the whole story. They are the antithesis of my story. I do not have first-hand knowledge of all the religious subjects Hitchens condemns, and no doubt many of them are condemnable. But in cases where I do have some familiarity, Hitchens’ characterizations are a cruel farce. He is all too economical with the truth. Were Hitchens to paint a more complete picture of people of faith, his credibility when naming their obvious failures would be all the more compelling.

3. The Love in Truth, and the Truth in Love

It should be clear by now that religious people will hardly feel romanced by Hitchens’ entreaties. Still, it can be an act of love to tell the truth, even when it hurts. There can be no mistaking Hitchens’ earnestness, his sincere belief that religion is a terrible force for evil in society. If Hitchens fails to tell the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, nevertheless there is much truth in his indictment of religion. Indeed, it is impossible to read god is not Great without being incensed. Even if many of his examples are dubious, enough are true enough that nothing less than outrage is appropriate. Considering his subject matter, his utter disgust is the natural response of a moral being to the frequent inhumanity of religious people across the globe throughout history. So, I do not doubt that Hitchens has the best of intentions. He believes that the diminishing of religion will be a good thing. Nonetheless, Hitchens’ hostility towards not just the worst of religion’s peddlers but to all the lost — the religious dupes and do-gooders — is a serious impediment to his message being received. As Anthony Gottlieb observes, “it’s possible to wonder… where plain speaking ends and misanthropy begins”. Be that as it may, shouldn’t the proclamation of truth be enough? The tender hearts be damned!

This mindset is described to a T by James Freeman Clarke.

To speak the truth, or what seems to be truth to us, is not a very hard thing, provided we do not care what harm we do by it, or whom we hurt by it. This kind of “truth-telling” has been always common. Such truth-tellers call themselves plain, blunt men, who say what they think, and do not care who objects to it. A man who has a good deal of self-reliance and not much sympathy, can get a reputation for courage by this way of speaking the truth. But the difficulty about it is, that truth thus spoken does not convince or convert men; it only offends them. It is apt to seem unjust; and injustice is not truth. Some persons think that unless truth is thus hard and disagreeable it cannot be pure. Civility toward error seems to them treason to the truth. Truth to their mind is a whip with which to lash men, a club with which to knock them down.1

There is a certain logic to this way of thinking. As a seeker of truth,I want it to be shouted from the mountaintops whenever it is found. And truth is no respecter of feelings. If I am satisfied merely by getting it off my chest, by having spoken my mind, then sure, the truth, as we see it, is enough. But if I care for those whom I think deceived, I will care whether the message is received. Perhaps another example will serve to illustrate.

The Religious Counterpart

As many observers have noted, the tenor of Hitchens’ commentary is in perfect harmony with that of many of the religious zealots he condemns. Some strains of Christian fundamentalism have a tradition of showing up at public gatherings with placards proclaiming what they take to be the urgent and prescient truth: “The Choice is Yours: Jesus or Hell.” “Global Warming is Nothing Next to Eternal Burning!” Invariably you’ll find a flock of offended passersby sparring with these heralds of damnation. The more inflammatory the placards,the more they serve their purpose to draw a crowd and begin the debate.I recently asked one such picketer why he didn’t choose a message more consonant with the emphasis of Jesus’ own teaching, something that could genuinely be called “good news”, something like: “The Good Life is Found in Jesus”, or, “Jesus is Water for a Weary Soul”. His answer was pragmatic. He admitted they’d tried it, but it just didn’t draw a crowd. He went on to argue for the importance of proclaiming the hard truth, no matter the response. No doubt these proclaimers return home with a sense of satisfaction, having done their “Christian duty”. Never mind that for every “saved soul”, ten turn away in disgust. “So be it”, they might say, “Jesus taught that the truth would be too hard to accept for many” (John 6). In fact, that is what they told me. So, Hitchens’ placard — “god is not Great. Religion Poisons Everything.” — will continue gracing books leaves on the bestseller shelves of stores across America and the street preachers will keep painting their dire warnings on bulk newsprint for their day trips across the state: two ships passing in the night.

Here’s the problem, as I see it. The problem is, Hitchens and his fundamentalist counterparts attend to the proclamation of what they deem the truth, but they fail to consider the conditions for it being received as such.

And So’s Your Mom

One of the most unfortunate but predictable human behaviors is to despise in return those whom we think despise us, even if for no other reason. The many years of French-American antipathy can largely be attributed to this tendency. Of course there have been historical offenses and differences of opinion one way or the other, but the average American who has never been to France nor parleyed with a Frenchman will often divulge a low-grade contempt for the French merely because he’s heard the French don’t think much of him. As a rule, when we feel dissed, we’re more than happy to return the favor. The mutual enmity this precipitates effectively makes dialog and persuasion almost impossible. It’s why the way of Jesus is again so acute: “bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you” (Luke 6:28). Jesus’ counsel reverses the spiral, returning hate with love, curses with blessing. No more perpetuating the tit for tat. An example of this took place, I think, at the Christian Book Expo where Hitchens joined a panel of Christian authors, each of whom bent over backwards to communicate how much they appreciated and were charmed by Hitchens. It’s amusing to watch, and to me, quite heartwarming. Even Hitchens expresses the warmest regards for the audience, quite out of character with his written words.

Another Way

Probably the most famous words on love are those in the thirteenth chapter of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. What is often missed is that Paul’s excursus on love is an elaboration of his teaching on speaking truth. Paul writes: “If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge … but have not love, I am nothing.” Paul makes the point, in memorable imagery, that truth without love is but noise to those who hear it. However profound and urgent, it doesn’t have the ring of truth. In a theatrical mood, I’ve pondered bringing my own set of cymbals to a public gathering to clang away, adding a soundtrack to the fundamentalist preachers of damnation, a way of raising Paul’s concern with some dramatic flair.

But, lest Paul be accused of throwing clichés about love, it’s worth considering how he spells out just what it looks like in this context.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.

Here we have a recipe for speaking the truth that could revolutionize the terrible state of uncivil discourse in society. To speak the truth in love is to speak with a spirit deeply motivated by goodwill for others, including one’s foes. In its patience, love perseveres through misunderstandings and frustrations. In kindness, it addresses sensitive issues gently, concerned above all to respect the dignity of persons. Divested of excessive self-importance, love is not bombastic, nor does it belittle or mock. Love is not brusque, but considerate and civil. Love does not quarrel for kicks, but because truth is urgent in a world where our actions have real consequences for good or ill. Prizing truth in all things, love does not caricature or misrepresent. Finally, love is optimistic. It assumes the best of others. It believes and hopes that dialogue will lead to greater peace and justice and human flourishing. Finally, love endures failures and setbacks, unflagging in its pursuit of the good.

One could be accused of a kind of Kumbaya naiveté for hoping for this kind of truth-telling, but I am convinced that love like this is the key to effective persuasion in controversial matters. In full view of the long history of philosophical, political, and theological disagreements that have led to violence, many have forsaken the enterprise of truth-seeking and truth-telling altogether. I too am weary of the debate, demagogic as it so often is. The only hope is another alternative, to rediscover the art of speaking the truth in love. Mastering this art will require being honest and disciplined in seeking truth, while also nourishing affection and goodwill for others in our hearts. It will require that we not be taken in by the demagogues who overwhelmingly populate the public square, and rather uphold and learn from those who embody Paul’s vision of telling the truth in love.

4. Show Us the Way

I have tried to be somewhat ironic in drawing upon Christian sources in this how-to guide for the critics of religion. Still, I think each of these principles are true, good, and effective. In yet another irony, if Christians themselves better followed these very principles, Hitchens would have written a very different book. His charges against Christians hit the mark far too often. As a Christian, I am deeply grieved and confounded by how often we fail to be like Jesus. Though I can object to many distortions and examples of poor reasoning in god is not Great, I am left with a yet deeper sense of this mystery that has troubled me most of my life. Disposed as I am to disenchantment with Christianity, Hitchens fails to capitalize on my doubts and of those like me because he so closely resembles the zealots he condemns. Dani Garavelli echoes this sentiment.

As regular readers of this column may know, I am not hugely devout, my faith, at its lowest ebb, being based more on a desire for God to exist than on an overpowering conviction that he does. If I were to lose the last vestiges of it and become an atheist, I suspect the most liberating aspect would be the prospect of jettisoning, once and for all, any association with the intolerance and invective that has blighted some sections of my own Church for so long. So it strikes me as odd that so-called movement atheists should adopt the very tactics they claim to abhor in religionists to further their own cause. (“Believe it or Not” at Answer The Skeptic, January 31, 2010).

Hitchens rhetoric is so full of disgust and absolutism, so lacking in empathy and nuance, that his irreligious vision of life hardly looks like the way to a new age of human peace and flourishing. And then I look back at Jesus. Though I and others who follow him fail to live as he did, at least in him I see a way of peace for which I can continue to strive. And then I notice that many who have risen to the defense of Christianity in response to Hitchens have done so with striking civility, care, respect … even, intelligence. Perhaps the way of Jesus does make a difference in some cases. My last suggestion for the critics of religion, then, if I may be so presumptuous, is: show us the way. Taking a mutual pursuit of truth for granted, by your example, also give me reason to believe that the shedding of my hopeful faith will make me less pitiful, less a shadow, more that person I want to be.

Notes

1James Freeman Clarke, Chp. 5 in Every-Day Religion (Ticknor: 1886), 63-76.